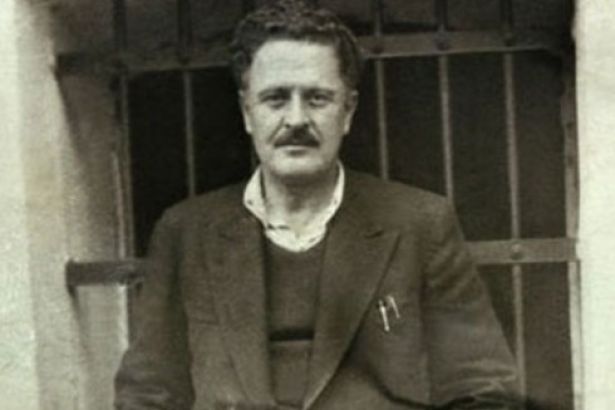

Commemorating 58th anniversary of communist poet Nâzım Hikmet’s death

The International Relations Bureau of the Communist Party of Turkey (TKP) commemorates the 58th anniversary of Nâzım Hikmet’s death. Born in 1902, the world-famous poet was a member of TKP. Nâzım Hikmet is one of the most important and greatest poets of the 20th century, still continuing to give hope with his works and strengthening the belief that “we will see good days.”

Commemorating the 58th anniversary of Nâzım Hikmet’s death

On January 15, 1902, Nâzım Hikmet was born in Thessaloniki which belonged to the Ottoman Empire at that time. In 1917, he was enrolled in the Ottoman Naval Academy in Istanbul. His first poem titled “Do They Still Cry at the Cypress Trees?” was published in 1918. On January 1, 1921, he went to Anatolia with his friend Vâlâ Nureddin to take part in the Independence War: Over the Black Sea, they went to Inebolu, from there on to Ankara; afterwards, he became a teacher in Bolu. The journey continued into the heart of the October Revolution where they reached Batumi in September and then Tbilisi.

In 1922, he studied at KUTV (The Communist University of the Toilers of the East) in Moscow. In 1924, he returned to the recently founded Republic of Turkey as a member of TKP in December. He sold “the Hammer and the Sickle” newspaper on the Galata Bridge in 1925 and was condemned to 15 years’ of hard labour. In the same year, he returned to the Soviet Union.

In 1928, upon receiving no answer from the Turkish embassy in Moscow whether or not he could return to his country, he secretly entered the country from Hopa. After serving a short term in prison, he began working at the weekly magazine named Resimli Ay in 1929. He started a campaign titled “Demolishing the Idols” against the prominent poets of the time. In 1930, a poet’s poems were recited for the first time in Turkey for a record: In this way, his poems such as “The Caspian Sea” and “Weeping Willow” were played with great enthusiasm in workers’ coffeehouses and open public spaces.

However, this enthusiasm was alarming for the record company, for the police forces and for some politicians. In 1933, he was condemned to a year of imprisonment with hard labour for libel by poem against his father’s employer, Süreyya Pasha. In addition, he was given four years’ of imprisonment with hard labour for forming an organization. He got out of prison due to the general amnesty granted to celebrate the 10th year of the Republic in 1934. 1930s remain as the period in which Nâzım Hikmet produced works in other genres aside from poetry, such as plays, librettos, film scripts and literary criticism.

In 1938, according to the prosecutor’s indictment, he was sentenced to 15 years’ of imprisonment on the allegation of “inciting the cadets to revolt” “with his works incensed with revolution and insurrection;” additionally, 13 years’ and four months’ of imprisonment for “spreading communist propaganda among the members of the navy and attempting to incite a revolt among the ranks of the navy against their superiors.” In total, he was sentenced to 28 years’ and 4 months’ of imprisonment with hard labour. In 1941, Nâzım began writing the series of poems, which he titled as “Human Landscapes from Turkey in Year 1941.” He matured and developed the style and approach he employed in “The Epic of National Militia” and “Meşhur Adamlar Ansiklopedisi” [The Encyclopedia of Famous Men], into what is now known as one of his greatest works, “Human Landscapes from My Country.” He transformed the prison cells he was detained in into schoolrooms and politically instructed writers and artists such as Kemal Tahir, Orhan Kemal, İbrahim Balaban.

In 1950, Nâzım Hikmet began a hunger strike in protest against the Turkish Parliament's failure to pass an amnesty law before it closed for the upcoming general election. He was persuaded to stop the strike by his lawyers after 15 days. On November 22, it was announced that he was the recipient of the International Peace Prize. Pablo Neruda received Nâzım’s prize, as he could not attend the ceremony due to his imprisonment. In 1951, he was set free.

Although he was discharged from the army on the invalidation due to pleurisy in 1918, as well as being 49 years old and a cardiac patient, he was summoned to the army. Being sure of the danger he was in, he left the country by a boat that sailed out from the Bosphorus. He returned to the Soviet Union. In 1958, he met with many writers and artists in Paris, such as Aragon and Picasso.

On May, 1961, he was welcomed in Cuba by his friend, poet N. Guillén to make observations on the Cuban Revolution, which took power in 1959, and the socialist transformations in place. The impressions from his Cuban travels were manifested in his poems titled “Havana Reportage” and “Straw-Blond.” The 60th birthday of the great poet, whose “poems were translated into forty languages,” was celebrated by the Soviet Writers’ Union. He returned from the Congress of the Union of the Writers of Asia and Africa with “Tanganyika Reportage.” On June 3, 1963, Nâzım passed away in Moscow.

Nâzım Hikmet is one of the most important and greatest poets of the 20th century. So much so that even his adversaries had nothing to say against his greatness and importance at the time when he lived, produced and fought, as well as thereafter. It was not only his poetic and literary skills that made him important and great: he built his greatness with his understanding of humanity, society and life.

He believed in equality, liberty, brotherhood and peace; as he never considered those concepts as perpetual longings or unattainable goals, he was ready to achieve them. He became important and great because he believed that being an artist and being creative are indispensable parts of the fight to free his country and humanity of their chains.

He began his political life by not surrendering to the occupying forces and always searched, learned and looked for ways of improvement and profoundness. He believed that the working class would be organized and become the sole force to defeat the “kingdom of the money, darkness of the bigot and the rocket of the foreigner.” He was politically engaged with this thought. Even in his darkest hours, he was determined not to yield, to stand tall and to labour.

By his own definition, he “wrote poems as much as the rainfall in one year”; in the most desperate times, he persistently searched for hope and at all costs, found it. With all his works, he still continues to give hope and strengthen the belief that “we will see good days.”