50th anniversary of Great Workers’ Resistance of June 15-16: Two epic days of Turkey’s working class

The working class of Turkey shook the entire country 50 years ago on June 15-16, 1970. Some of the capitalist patrons fled abroad for fear of workers who stopped all life in the country from the north-western industrial province of Kocaeli to Istanbul for their rights against capitalism and anti-labour policies imposed by the Turkish government. What happened in those days also brought many political and theoretical discussions in its wake.

We interviewed with Alpaslan Savaş, the Central Committee Member of the Communist Party of Turkey (TKP) and the unionization expert of the United Metal Workers’ Union of Turkey (Birleşik Metal-İş), regarding the conditions that paved the way for the resistance, the vanguard of the two epic days of Turkey’s working class, and its political/theoretical significance for today’s working-class movements.

Can we describe the Workers’ Resistance of June 15-16 as one of the brightest moments of the class struggle for the working class of Turkey? There was a sharp distinction and direct class antagonism between the working class and the capitalist class. Such a confrontation had never been so clear in the history of Turkey.

Definitely it is true! The labour movements had already been on the rise in Turkey during the 1960s. In this period, many national, regional and workplace-based workers’ protests occurred, especially for the demand of the right to strike. Thus, the class struggle in Turkey had already become sharp until that day. The 1960s was also a period that the socialist movement of Turkey was organized more within the working class, making its presence felt like a social alternative.

If it is necessary to briefly remind, what happened on June 15-16, 1970?

The development that sparked the Resistance of June 15-16 was the adoption of a draft law prepared by the government to stop the rise of the working-class movement in Turkey. The draft law had proposed a series of amendments to the laws designating union rights. These amendments targeted the Confederation of Progressive Trade Unions of Turkey (DİSK), founded in 1967.

Five labour unions accused the Confederation of Turkish Trade Unions (Türk-İş) of losing their independence and collaborating with governments serving in the interests of the capitalist class and left the confederation to found DİSK.

As DİSK managed to become a centre of attraction for workers in the country, there was also another important point in the foundation of this confederation: A significant part of the unionists who led the establishment of DISK was founding members of the Workers’ Party of Turkey (TİP) in 1961. In this respect, DISK represented a progressive movement in the workers’ struggle in Turkey.

DİSK, as a centre of attraction for workers, inevitably became the target of the capital class. A draft law was prepared to hinder the rise of DISK among the working class of Turkey. This draft law, prepared with the support of yellow union Türk-İş, imposed an obligation that at least one-third of the workers in the lines of work had to be members of the relevant unions in order for unions to carry out activities nationwide. This threshold would have caused DİSK and its affiliated unions to become unorganized and unable to represent workers in fact.

What were the conditions paving the way for the Great Workers’ Resistance of June 15-16? If you can explain it by focusing on the recent past of the events, the dynamics that ignited the wick of those days can be better understood.

In order to understand such a massive working-class movement, it is useful to take a closer look at the decade between 1960 and 1970. Let’s briefly remind the events that distinguished in the workers’ movement until the Resistance of June 15-16.

First of all, we can mention the importance of the Saraçhane Rally in Istanbul. This rally in 1961 was the first prominent massive working-class demonstration of the period we are talking about. The primary aim of the Saraçhane Rally organized by the Association of Istanbul Trade Unions (İİSB) on December 31, 1961, was to create pressure over the government for the legitimation of the right to strike without any restrain, which was actually recognized by the 1961 Constitution. We can say that the Saraçhane Rally represents the beginning of the rising working-class movement of the 1960s.

Workers in Turkey carried out many protests by occupying their workplaces and actual strikes in the years following the Saraçhane Rally. The most important one among them was the Kavel strike. The Kavel factory was owned by Vehbi Koç, one of the richest capitalists in Turkey. The Mine Workers’ Union of Turkey (Maden-İş) was organized in the workplace. This union would leave Türk-İş a few years later and be among the founding unions of DİSK. Vehbi Koç wanted to revoke some crucial rights of workers in collective bargaining, especially the bonuses paid to workers. In fact, his primary aim was to get rid of the union. Upon this, the workers in the Kavel factory went on a strike in 1963. This strike was the pinnacle of the struggle for gaining the right to strike a legal status for workers in the country. Local people living in İstinye and its surroundings ─ where the Kavel factory was located ─ gave great support to the resisting workers. Despite the redundancies, use of violence and arrestment by the gendarmerie, the workers decisively continued their struggles for rights.

The Kavel strike accelerated the introduction of two new laws that regulated the right to strike within the context of the 1961 Constitution. In the same year, Law no. 274 on Unions and the Law no. 275 on Strike and Lockout were discussed and approved by the Assembly. However, the right to strike in the laws adopted in the Assembly was not defined as broadly as it was included in the 1961 Constitution. The workers’ struggle for the scope of this right continued in the following years.

During the decade before the Workers’ Resistance of June 15-16, there were many momentous labour protests that can be called ‘‘unprecedented’’ in the history of Turkey.

One of them is the demonstration of the unemployed that took place in 1962, called ‘‘the March of the Starving People’’. On May 3, 1962, approximately 5,000 workers and the unemployed, mostly construction workers, gathered in front of the Federation of Turkish Construction Workers (Yapı-İş) in Ulus district of the capital Ankara and marched towards the Grand National Assembly of Turkey (TBMM). Although the governorship did not allow the march, law enforcement forces could not stop the workers and unemployed people, struggling for their rights. Such a massive protest of the unemployed took place for the first time in Turkey’s capital city of Ankara. Upon ‘‘the March of the Starving People’’, the Assembly had to discuss the unemployment problem in the country and took some decisions to deal with it.

This period had also witnessed many occupations of factories as a method of the workers’ movement used to prevent lockouts.

Two years after 1968, workers struck work at dozens of production plants and occupied the factories for their demands. Alpagut Coal Enterprises, Derby Tyres, Emayetaş Factory, Singer, and Turkish DemirDöküm factories are the most known of the occupations.

In some of the occupied factories, workers even took control of the management and continued production to pay for the workers’ salaries unpaid by the bosses before the strike.

Furthermore, we bear witness that a part of the working class employed as civil servants within the state institutions also included in the organized labour movements actively during this period. Many unions for public employees after 1965 were founded, as the most effective of these unions, was the Teachers’ Union of Turkey (TÖS). TÖS managed to mobilize tens of thousands of teachers in a short span of time, while both massive student and teacher-led boycotts took place across the country.

What happened in the past regarding the workers’ struggle for their rights is very important. Can we consider all this development as both qualitative and quantitative transformation for the working class of Turkey?

As you said, these are all extremely important events. They made a great impact, playing a role in the development of a ‘‘class identity’’ among the working class in Turkey. Thus, all these events actually mean that the working class has become more organized. For instance, workers occupy the factories or organize massive rallies for rightful reasons and motivations. All of them are struggling for their rights against the capitalist class and the state continuously trying to exploit workers to maximize their profit. Yet, workers’ actions definitely correspond to an organized struggle.

In other words, when we say that ‘‘the working-class movement is rising’’, we also refer to the increasing organization of the working class. Similarly, an organized working class mobilizes faster [and stronger]. They stand tall and resist the oppression of the capitalist class. And all this cycle enables the working class to take the lead more powerful in such movements as a social class.

It is surely beyond doubt that a well-structured, deep analysis of the previous decade to understand the Great Workers’ Resistance of June 15-16 is very important. Could you give some more details on it?

In all these events I told above, we can say that the two major events marked this decade before the Resistance of June 15-16.

One of them is the establishment of TİP in 1961, and the other is the foundation of DİSK in 1967. The founders of TİP were unionists, who also established DİSK exactly four years later on the same day. Most of them were not communists. Yet, they were the next representatives of the union movement led by communists in the late 1940s. We can say that they were the unionists who struggled against the state apparatus trying to control unionization both within the legal framework and with the U.S. support. The first figures that come to mind are Kemal Türkler, İbrahim Güzelce, and Avni Erakalın… These union leaders, who founded TİP, decided to take the left-wing/progressive intellectuals’ advice a year later. Those communist intellectuals turned TİP into a real political party, indeed.

TİP had become the home of egalitarian Alevis, libertarian Kurds, politically active university students and leftist intellectuals in a short span of time.

By June 15-16, 1970, there was a labour union that became the centre of attraction for the working class and a party that was politically representative of workers in Turkey.

The result of the developments I have told so far can be summarized as follows: On the eve of the Resistance of June 15-16, the working class of Turkey had become quite strong with the ability to voice its social demands and to claim its rights. On top of it, this ability had emerged despite all the inadequacies in left-wing politics and the union movements.

It is quite ‘‘normal’’ that the rise of the working class as an assertive social entity extremely disturbs the capitalist class. Hence, the development that sparked the Resistance of June 15-16 was the capitalist class seeking for certain measures to intercept the rise of the working class. The draft law that we mentioned at the beginning, which meant intervention in the unionization of the workers, came to the agenda in this way.

Half a century has passed since the resistance. What kind of conclusions can be drawn from the Great Resistance of June 15-16 under the contemporary circumstances of the working class of Turkey in 2020?

In order to understand it more clearly, we can formulate these two questions: ‘‘What made this resistance so powerful? Which features increased the impact of this workers’ struggle so much?’’

First of all, the geographical expansion increased the impact of the Great Workers’ Resistance of June 15-16. In 1970, Kocaeli and İstanbul were the two cities considered the heart of the industrial production in Turkey. And these two industrial provinces represented a large geography for such a movement.

Secondly, the resistance was mostly based on workplaces and factories. When I say ‘‘workplace-based’’, I mean that the strikes and protests were organized and started in the workplaces and factories. The participation in the strikes organized in workplaces was high, well-disciplined and decisive. Therefore, it was difficult to incite provocation in such protests and weaken the workers’ resistance.

Thirdly, the Resistance of June 15-16 had spread among various sectors. Although the dominancy of factories in the metal industry is indisputable during the resistance, workers from other sectors such as petro-chemistry sector, tire industry, pharmaceutical industry and food industry had also joined the strikes in the region. Therefore, the resistance had a general character, not sectoral.

And lastly, all labour unions without any favouritism had fully participated in the protests. In the resistance, there were workers who were the members of DİSK, which would have been directly affected by the government’s draft law, but the workers affiliated with Türk-İş, who played a role in the preparation of the draft, also participated in the protests.

So, we see that the workers struggled together for their rights during the Resistance of June 15-16, regardless of their membership to confederations.

All these features of the Resistance of 15-16 June make it unprecedented and impactful. Most importantly, it shows that the strike was based on the unity of the working class.

Of course, DİSK, which was at the target of the draft law, played a great role in the resistance. Yet, the protests did not start and did not continue exactly as DİSK had planned before. We must underline that the workers’ resistance on June 15-16 exceeded the impact of the union centre many times more.

Considering the left-socialist movements of the period, we observe that although there were many left-socialist organizations, none of them could pioneer the working masses to influence the protests, including TİP.

So, who organized this resistance? We find the answer to this question at the workplaces. The most significant work accomplished by DİSK between 1967 and 1970 was ‘‘workplace unionism’’. Unlike Türk-İş, DİSK was organized by visiting workers at their workplaces and factories. In this process, workers leading to struggles in factories along with unionist cadres began to come forward. In fact, DİSK created a political and assertive grassroots that exceeded itself. This was the nucleus of the Resistance of June 15-16.

The resistance strongly revealed the assertive and challenging identity of the working class, which began to blossom forth over the course of many years. This is indisputable. On June 15-16, the working class of Turkey showed that the hegemony of the capitalist class was not so invincible. This situation has also helped workers to realize their own power.

The Great Workers’ Resistance of June 15-16 was also a definitive answer to the critical questions of ‘‘Is there a working class in Turkey?’’ or ‘‘Can we talk about a working class that is capable of leading a revolution in the country?’’, discussed by the left-wing movements in Turkey at that time.

‘‘Yes, there is the working class in Turkey and this class is powerful enough to shake this capitalist social order,’’ the working class of Turkey answered such questions with the Resistance of June 15-16, 1970.

We know that capitalist patrons were very concerned about the workers’ resistance during that period. The most striking evidence of this tremendous fear caused by the resistance in the capitalist class was that a considerable number of bosses had fled abroad for the fear of ‘‘revolution’’ when the protests began.

Whenever the organized working class demanded more and did not settle for the pseudo-concessions given by the capitalist class to silence workers’ rebellion, it always triumphed in its struggle for rights. ‘‘More’’ is now the political power of the working class.

If the working class of Turkey demands less than the dictatorship of the proletariat, it will have to settle for the breadcrumbs deemed proper for workers by the capitalist system. The century we left behind was filled with examples of such stories for the working class. And the Resistance of June 15-16 also affirms this.

Besides, the Great Workers’ Resistance of June 15-16 is a testament that the capitalist order in Turkey doesn’t have absolute power, the capitalist class is not invincible, and the workers do not have to rely on bosses. The political power of the working class is possible and necessity now. This is the summary of our lesson for the Great Workers’ Resistance of June 15-16.

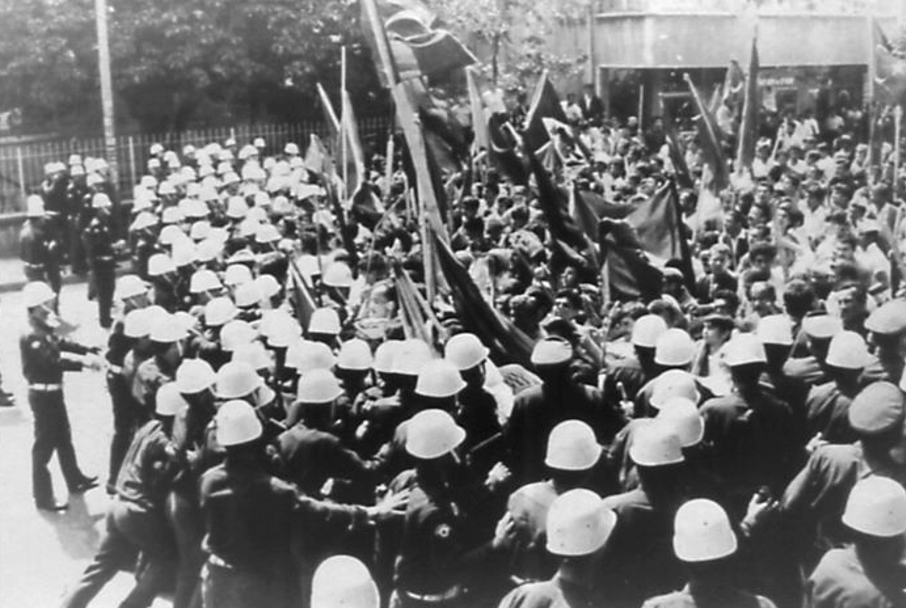

Photo by Mehmet Demirel, Hürriyet Newspaper, From the Resistance of June 15-16, 1970.